This is a story of self – place, loss and memory.

Storytelling is one of our defining characteristics, a means of passing knowledge from one generation to another. Without it, much would have been lost to us over the many thousands of millennia we have walked the earth. I admire those that can creatively use language to engage, inspire, enthuse and communicate – as I often am when reading their works. But for me, the power of the spoken and written word often fail me when I come to use them. I feel clumsy and awkward with their use; they don’t come easy to me. I see what I want to say clearly enough in my mind, but often unable to translate that to language.

Why start with this self-confessional? Well, my language skills were to pose me a quandary and opportunity all at the same time for my Cubby’s Tarn body of work. Two years into a four-year project it became clear I was going to have to face my demons head on and sharpen my pencil. A series of images would have served very well for my original intent, but I realised there was a far more important story to tell here than an exploration of my own fascinations for a subject, and that needed to be written down. The story of many that have passed before, who managed and nurtured our land and wildlife sustainably for future generations. A story told through the recounting of one man’s life. Someone who would embody the noble acts of man’s intervention in the landscape. A story woven with my own and many others, influencing the paths many of us would take in life. That man is almost certainly unknown to this audience; his name is John James Cubby MBE, the former Forestry Commission Chief Wildlife Ranger at Grizedale Forest in the English Lake District.

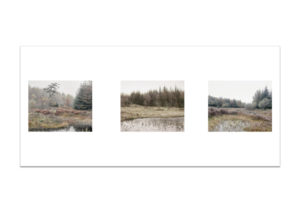

‘This is a landscape far from being untouched by man, despite the initial impressions this is most definitely not a wilderness. Yet nature survived, more, it was encouraged to flourish by many who’d come to realise the true value in doing so was a revitalization of the landscape. Not least of these was John Cubby after which it [The tarn] is now named.’ – Quote from the prologue written by Rob Hudson in Joseph’s book, Cubby’s Tarn.

I don’t intend to tell ‘Johnnies’ story here today though; it would take too long and I think not do it justice and not necessarily the point of this article. That’s for my book of the work, after all, that’s what books are for. I think it’s enough to say, the story of ‘Johnnie’ is the story of an ordinary boy who developed a passion for nature and wildlife, and who in adulthood dedicated his life to improving wildlife management practices in the developed world day. Sharing his knowledge and passion with the many thousands of children and adults he met throughout his life, many of whom cite John as one of the driving forces in taking up nature or countryside related vocations and interests – myself included.

With Cubby’s Tarn, what began as a journey of my own search for and exploration of the genius loci – the long held notion that places can have an abiding protective spirit – ended with the creation of my own metaphoric visual eulogy and written documentary. In allowing myself to keep open minded and allowing the work to take its own course I created what I feel is a body of work which best represents my own ethos about photography. Overcoming my own limitations with language in allowing photography to be my voice. Like all art forms and media, photography provided me with a tool. In the way that we use image making, it shows the world who we are, whether we are being true to ourselves or not, it exposes us for what we were at that moment of ‘releasing the shutter’. Our thoughts and intent, our truths, our opinions.

The Genius Loci ‘Spirit of Place’

(extract from the book Cubby’s Tarn)

‘Walking up the access path to Cubby’s Tarn for the first time on a misty overcast morning, brushing past dew laden branches and through the wet spidery webs, it was hard not to be struck by the fluorescing late autumn colours enriched by the dampness from the overnight mist. Yet it was not the immediate visual feast, the physical act of looking and wanting to see more that was drawing me further up the path. There was something else pulling me forward – it was a psychological experience – what I believed I was sensing that morning was the genius loci; the ‘spirit of place’.

I sat that morning for a while inside the wildlife hide, on a mossy knoll above the memorial stone dedicated to John James Cubby MBE, looking out across the natural amphitheatre of the forest glade in which the tarn nestles. Out across the tops of the plantations towards the fells in the Furness Ranges. A ritual I would repeat in solitude over several years for many more times to come. In doing so I sought to understand more about this mysterious genius loci that gripped me on my first and subsequent visits to the tarn.

I was sure there was more at play here that was intriguing me, more than simply the recognition of the dedication to John and his influence in this part of the English Lake District. More than the fact my parents had formed a lifelong friendship with John, forged through both a working and personal relationship with him that began the year of my birth; 1963, when he arrived at the farm where my parents lived and worked at the time. More than the memories of our family stay at Grizedale with John where I explored the fields, beck and forest fringes beside his then home; The Kennels.

I have long been fascinated with our connection to the land. To places; the past and present, how we have shaped and influenced its use, and of how it has shaped and affected our lives at both a physical and spiritual level. But one area that has intrigued me more than most is this notion of the genius loci. I am certain this is something we all experience, but perhaps not all understand or believe of its existence; that innate feeling of connectedness we experience when visiting places, even in lands foreign to us. Quite often locations unfamiliar, with certain landscapes exerting greater influence than others.

Genius loci has been explored through many art forms over the years. It has been suggested the concept in some form originates 5000 years ago to the Pre-dynastic period of Ancient Egypt. However, the current use of the name has Latin origins, which can be traced back to its use in classical Roman religion. In that time, many places such as rivers or woods had named spirits, inferring the existence of a protective force. Where there was no identifying spirit for a location they were generally referred to collectively as the genius loci. These views are still practiced in many parts of the world today, particularly in Asia.

In the western world, a more contemporary use of the term genius loci could be best described as expressing ‘atmosphere’ intrinsically connected to a place. Something that is experienced rather than necessarily exists, which perhaps shifts us more to ‘sense of place’. Some believe this comes from that ancient belief of the ‘land’ itself; trees, rocks, water, sky… having ‘spirit’, and it this that we are sensing.

Others, like myself, believe what we sense in circumstances like these is a personal externalisation of deeply seated emotions, experiences, memories, that have over time shaped and influenced our conscious being – the person we are – triggered through some recognition of an aspect of the place. Over the period I visited the tarn I came to understand, for now, genius loci could be best summed up as the manifest collective of history, culture, the past and present. As such, it grows within us as we age and experience the world around us, and roots us back to the earth.’

In Memory of John James Cubby MBE, d. Oct 2007.

‘The spirit of this place’

Excerpt from the music piece composed by Richard Skelton. The full 15 minute EP can be heard at the Cubby’s tarn exhibition, more details further down.

Cubby’s Tarn is currently being exhibited at the Grizedale Centre as part of Forest Art Works, a new partnership between Arts Council England and Forestry Commission England. For more details see the event details on Joseph’s website or the Forestry Commission’s Grizedale website

Cubby’s Tarn Exhibition

Grizedale Forest Centre

Nr. Hawkshead, Cumbria

LA22 0QJ

18th October – 31st December 2017

BOOK

The book for the full body of work for Cubby’s Tarn is available to purchase from JW Editions

|

|

|

|---|

Joseph Wright (b. 1963) originates from Cambridgeshire, but is now based in a small village near Swindon in Wiltshire and has spent much of his life living and working in semi-rural locations. His artistic work includes photography and book making, firmly of the opinion that photographs are best viewed in printed form, preferably books.

He is best known for his evocative and multi-layered landscape images that reveal stories of the land, how we inhabit it and how it affects us, developed through an understanding coming from his life long relationship and deep affinity with the countryside and edgelands. His work is instinctive in response to place and event. It is frequently rooted in history, toponymy and topography. He unwinds time and peels back the layers of culture and memory creating work to move beyond the simple aesthetic to reveal a deeper understanding of his subjects.

Joseph has recently exhibited as part of a group show at the MMX Gallery of contemporary photography in London and has also had work shown in the international contemporary photography award Fotofilmic ‘16 which has toured Los Angeles, Vancouver and Melbourne.

He is a founding member of the Inside the Outside (ITO) collective.

Website: josephwright.co.uk

Twitter: @JoeARWright

Twitter: @JoeARWright

Joseph is also the founder of JW Editions; an independent publisher of photobooks, who produce short run commercially produced edition based releases and handmade limited editions.

Website: jweditions.co.uk

CREDITS

Cubby’s Tarn music © Richard Skelton – Website: corbelstonepress.com

Unless otherwise stated, all words and images in this article are © Joseph Wright