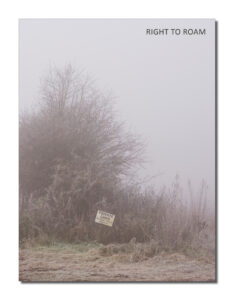

This mini feature showcases one of the eighteen open submission portfolios selected for inclusion in our printed journal based on the theme of the right to roam

I am a settler living on the north shore of Lake Ontario on the traditional territory of the Misi-Zaagiing Anishnaabeg, lands covered by the Williams Treaties. Although I was born here, just east of Toronto, I am not indigenous to this land. I am the product of a settler state. My continued relationship to this place, my responsibilities and rights, including any right to roam, are first predicated upon my respect for the treaties.

Here, in the shadow of the uranium refinery, the Ganaraska River empties into Lake Ontario. I head east along the open-access beach well out of sight and reach of buildings. At the lakeside I am small and transient against physical forces and the longer, slower currents of geological time. In every grain of sand Rachel Carson saw a story of the earth. Repeated glaciation. Laurentide ice more than a kilometre thick. Melting, weathering, scraping. Mineral deposits of quartz and feldspar. In every grain of sand, a story. In every grain of sand, a world.

I walk the shoreline, ducking back to the parallel trail when an obstacle blocks the way. Two years ago, high water and storm pushed waves of beach stone deep onto the trail. Volunteers cleared the trail. But at the shoreline, trees once firmly rooted became unstable when water undercut them. Now that the lake levels are low, many of those trees have fallen. At the water’s edge I pass gnarled root platforms stretching toward the sky and out over the water. Stones are wedged in clefts and crevices, beetles walk the twisted roots, and mosses take hold. Transformation.

Sometimes I roam the west beach, south of the railway embankment where both weather and aspect are wilder. Sheltering from the cold or the wind, I follow brief pathways lined with grasses, dogwood, birch, and cedar. A few days ago, I saw a bushy red fox emerge from the undergrowth and lope along the sand.

As I make my way west, I am careful underfoot, each step a small revelation, a limestone pebble just there, a runic stone, trilobite and crinoid, a bone-branch. My disordered thoughts soon fall into the rhythm of rolling waves and weather. The disquietude and worry I have carried through this pandemic settle for now. My experience of roaming is never a surrender of self; rather, it is a lucid becoming, a restoration of balance during uncertain times. Sorrow and loss, and all we think when we think forward or back, give way to a peaceful string of nows, gathered and sorted the way the wind and waves sort the pebbles and stones on shore.

My photographs, a record of both roaming and hope, span the pandemic through every stage of lockdown. This is where I live, on the traditional territory of the Misi-Zaagiing Anishnaabeg people where the Ganaraska River feeds into Lake Ontario.

The full set of images from the open submission are shown below (click to view image larger in the original format).

CREDITS

Unless otherwise stated, all words and images in this article are © Margaret Poynton

THE JOURNAL

Our biggest, most content packed, and socially current publication to date, exploring the theme of the right to roam. Featuring an introduction by our very own co-founder Rob Hudson and a selection of work from 37 contributors, including the one featured above. Click on the image of the journal cover below to take you to the journal’s information and ordering page.