The many times that I have wandered these extinguished and drained landscapes, I have been the only human presence within a hinterland totally created by human toil. By dint of their purpose, they are often epic vistas, littered with the relics or ghostly remains of industry on a huge scale; machinery, bricks, slag heaps and empty, shattered buildings. Where now is just bird song and the breeze, I hear once deafening sounds, and see beetling figures and never-ending work. Now, where there is just nature, growth and decay, I hear toil 24 hours a day, filling the air with smoke, ashes, fire and sparks; a permanent orange glow of an artificial daylight.

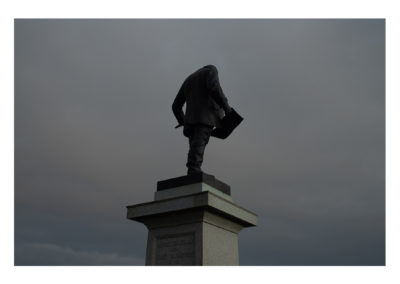

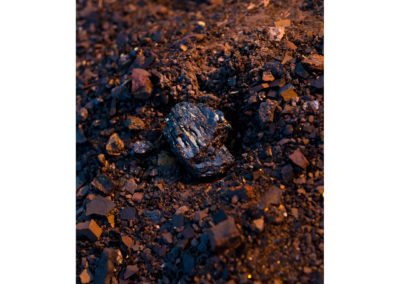

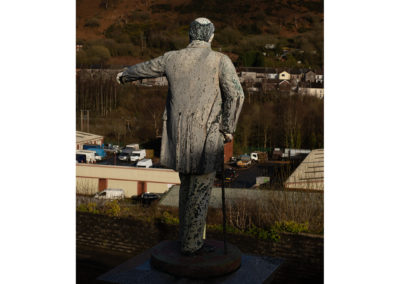

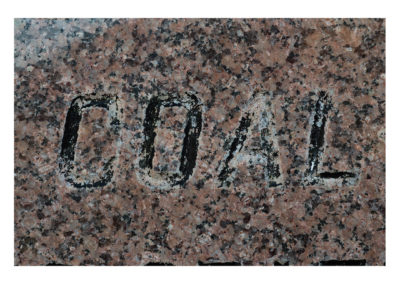

An accident of circumstance left raw materials of innocuous appearance in these lands; I ask myself who first noticed them, held them to the light, and realised their potential? And then, many years later, who imagined mining, digging, damming, burning and smelting them on an industrial scale? Who put together huge works, factories and the personnel to supply materials for the rush of technology and innovation? Who saw rural communities, unchanged for centuries, and envisaged them obliterated by these works? These figures are now lost to time, titans of an age shrouded to us by the passing of hundreds of years. Their factories and mines, monuments and earth works are now returning to the nature they came from, and the mounds and burrows and quarries are as desolate as when these ‘Captains of Industry’ first saw the lands that bore them. Did this new nobility, from their viewpoint of unprecedented status and wealth, ever see a lifespan for their plans that ended as ruins in a wasteland?

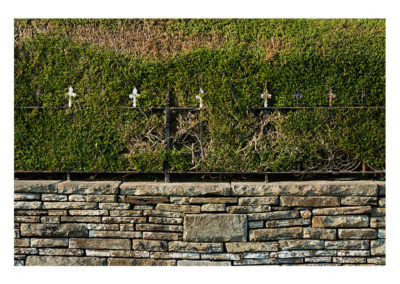

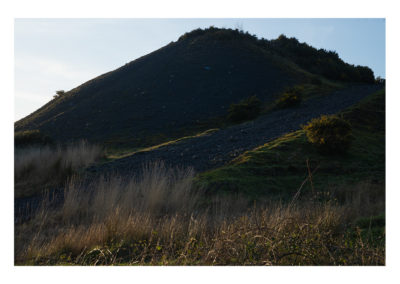

I ponder why I am drawn to these spaces. Liminal and ambiguous, there is a fascination in stumbling across the incongruous within a wasteland. To the untrained eye these vistas are now a mystery, softened and shrouded by time, features hidden within the scenery. They are about the trace, the hint, of something much grander, a time ‘before’. Dangerous edifices and whole landscapes have been rearranged, buildings vanished, and machinery cut up for scrap, but a malign and oppressive force remains in the landscape. Spoil tips replicate the presence of the Pyramids, ultimate signs of power of the Pharaohs. They mimic too the burial mounds of many communities, and in that they embody power and death- the power of the mine owners and industrialists over the workforce, and the death of their own era. They are emblems of exploitation- of land and humanity, in just the same way that the Pyramids were.

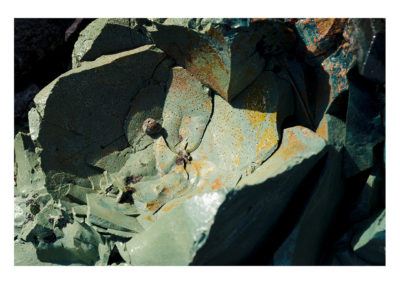

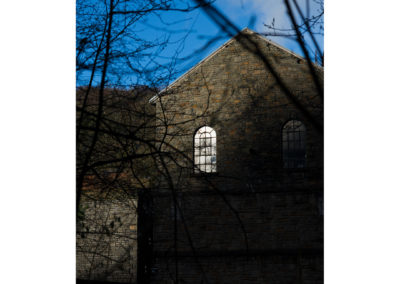

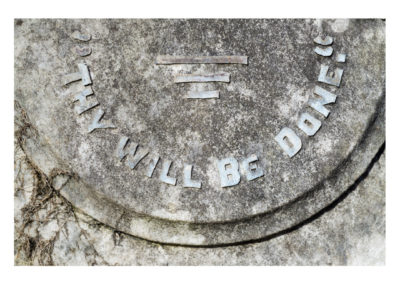

These areas are often at the edge; the edge of a town, the top of a mountain, or a beach or river. The spaces are haunted by absence, retaining elemental traces of the past. Being on the edge of spaces allows you access to the different layers, like a wall painted many times- the edges are frayed. Objects within them are more than just what they are; becoming totemic symbols of layered history, an assemblage of narratives. They become monuments to their own passing, but also useless and surreal, divorced from purpose and context- bricks separated from walls, door handles separated from doors, upturned reliefs of slag, tipped from ladles and solidified by the sea. Time is what gives these landscapes their potency, the sheer weight and stretch of time. From the forming of minerals and elements, to their eventual unnatural re-emergence, to the closure and decay of works and even whole vistas, time crushes everything.

Images from the series are shown below (click to view image at full size / original format).

ABOUT JON POUNTNEY

Jon’s love of photography was propagated and then nurtured by his grandmother Olive. He was encouraged to use his grandfather’s vintage Voigtlander for experiments with double exposure and trick photography, and then in 1995, for his 17th birthday, she bought him a second hand Olympus OM10, which he still uses. Growing up on a farm in rural Warwickshire and going to college in Leamington Spa meant that his subjects were those landscapes and times spent with friends; a sense of place and time was already very important within his work. In finding vernacular and municipal architecture intriguing and attractive, a beautiful town like Leamington was a great place to foster a growing interest in creating a ‘genius loci’ in his work.

On moving to Cardiff as a student in 1996, he encountered a totally alien landscape to the rural fields and woods he had grown up in. In response, he threw himself into using the college darkroom, working mainly in black and white, seeking to reflect the drab cityscape. Jon became totally self taught, there being no photography tutor on his course; influences at the time were Ian Berry’s book ’The English’, and Don McCullin’s work in Britain. Later influences were Richard Billingham, Juergen Teller and Wolfgang Tillmans, but his work has always been more about a wistful dislocation of time and a sense of nostalgia than contemporary social documentary.

Website: jonpountney.co.uk

Instagram: @jonpountney

Twitter: @JonPountney1

CREDITS

Unless otherwise stated, all words and images in this article are © Jon Pountney